| Back to Back Issues Page |

|

|

Real World Physics Problems Newsletter - Exoplanets, Issue #17 March 25, 2015 |

Life On Exoplanets

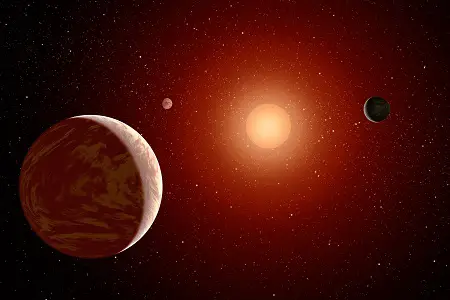

https://www.real-world-physics-problems.com/images/red_sun.jpg Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Perhaps the most likely stars to contain life-bearing planets are red dwarfs. They are by far the most common types of stars within the Milky Way, and they have a very long lifespan, much longer than that of our sun. The lifespan of our sun is 10 billion years, while the lifespan of a red dwarf can be as much as 10 trillion years. The extremely long lifespan of a red dwarf increases the possibility for intelligent life to evolve on a planet that orbits it. It has therefore been suggested that red dwarfs are the best star candidates in which to search for alien life. Life on an exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star would probably look very different from ours. The brightness of a red dwarf is much less than that of our sun, so life on red dwarf planets would have to evolve ways to survive in the presence of lower solar radiation. Plant foliage, for example, would probably be black in color in order to absorb as much solar radiation as possible, and enable photosynthesis to occur. Detecting the presence of habitable exoplanets orbiting other stars is not easy. It takes highly specialized equipment and sophisticated analysis techniques. One way is to observe how quickly exoplanets orbit their parent star, in those instances where the plane of the orbit lies in our plane of view. Every time the planet passes in front of its parent star, the light from the star reaching us diminishes a tiny bit. This slight reduction in star brightness can be detected by the Kepler space telescope which actively looks for exoplanets. The degree of reduction in brightness can be used to calculate the diameter of the planet, and the time interval between passes (in front of the star) can be used to calculate how large its orbit is, and based on this, what the approximate surface temperature of the planet might be. This in turn gives an estimate of the probability that this planet can harbor life as we know it. Indeed, there may be

40 billion, or more, such planets in our galaxy alone, meaning Earth is far from unique.

|

| Back to Back Issues Page |